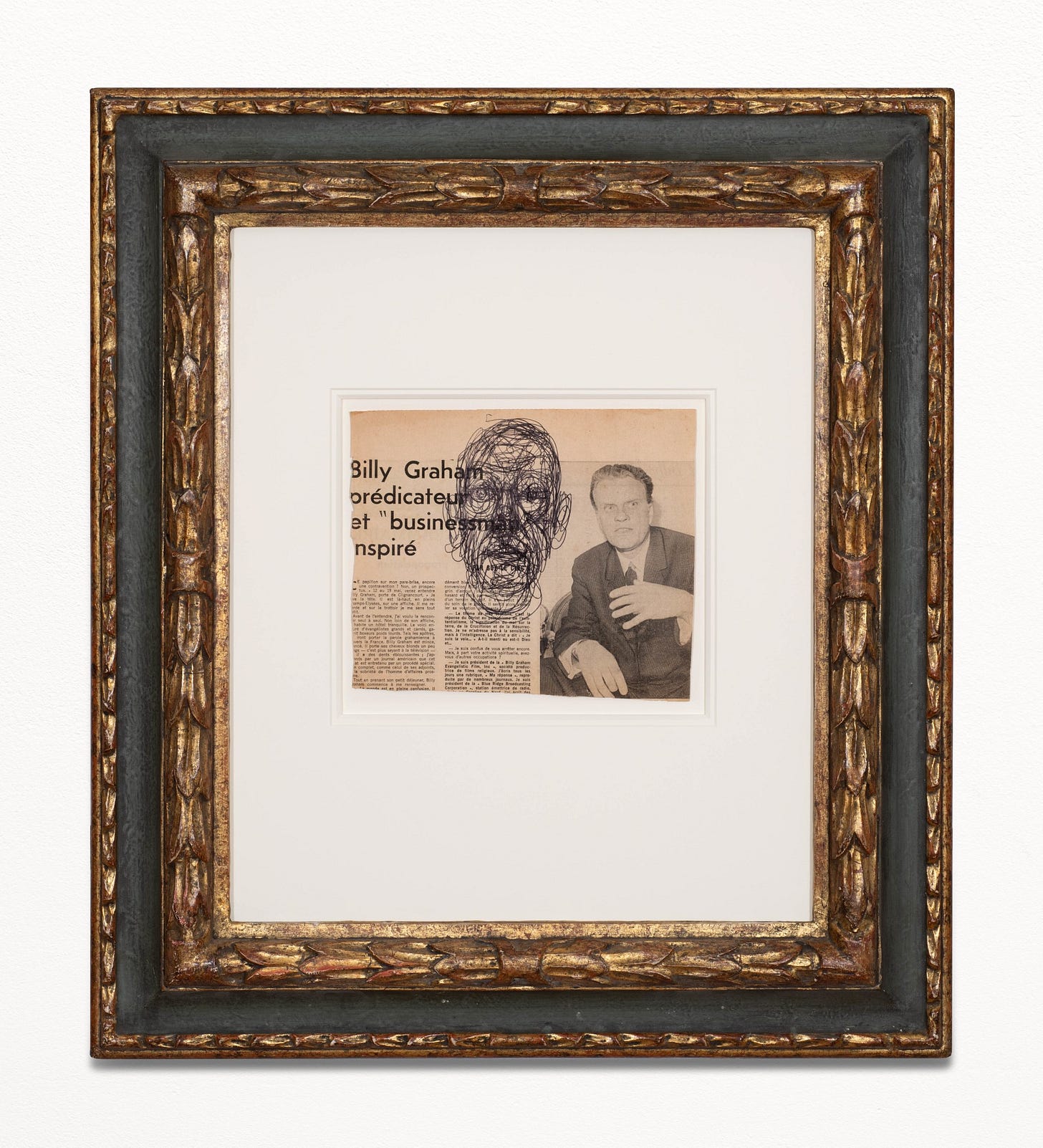

Alberto Giacometti. Tête d'homme, 1963. Ballpoint pen on newspaper.

This coming weekend in St. Moritz is one of the best of the year, with events from the ICE car event on the lake to NOMAD. At NOMAD, visitors roam through whatever available building (this year it will be in the former building of the renowned Klinik Gut) and discover paintings, ceramics, vintage pieces for the house (catalogue here), and the half of Milanese society who decamp to the Engadin in the Winter months.

The artwork that captured my attention most at NOMAD 2024 was Alberto Giacometti’s wild scribble of a man’s head on a newspaper clipping about Billy Graham (shown above). The piece was likely uninteresting for others, apart from it being a Giacometti, but it brought me delight. I was delighted with a number of things:

it seems to poke fun at Graham and our collective earnestness about our identity (the American missionaries in Indonesia who ran my boarding school worshiped Graham),

it feels like a moment of self reflection on Giacometti’s part while doodling on a piece of newspaper in his messy workshop. The eyes, despite being but a scribble, have an element of despair and questioning in them: the fragility of life, the searching for meaning….

its impulsive execution reveals our human drive to create,

and, it is technically interesting because it is done in one continuous movement —no breaking of the line.

Despite its simplicity the piece is for me a strong study on identity and how we participate in our world: what we believe, what we do, what we perceive, and what we identify with. How we see ourselves and others is both through imagination and technical knowledge. We are quick to use the word relationship when referring to how we know others, but if we stop to consider what we are saying, we care confronted with something intangible. We know ourselves — and yet not really. We know others— but only in part. We certainly do not claim to use mere imagination to understand others; we need the facts of their lives and the context of their world to know.

It keeps occurring to me that this is also how we need to consider how we relate to life itself: we live in an era of techniques, and facts, and technology; but the more we focus on these simple facts, the more we park our imagination in a dark corner of our lives, and hope that we will reach truth through the distilled facts of our times.

Owen Barfield’s excellent book, Saving the Appearances, which lends its name to the title of today’s post, calls for true participation in our world through the pre-rational, the rational, and the trans-rational. In other words, it is our imagination that allows for full participation in our world. Imagination is necessary for both perception and understanding. If we reduce our observations to an “I-it” relationship, we risk idolizing facts, detaching ourselves from the world rather than participating in it. (We are largely in this kind of society, today, I’d say.) “The systematic use of imagination, then, will be requisite in the future, not only for the increase of knowledge, but also for saving the appearances from chaos and inanity,” Barfield wrote.

Knowing for ourselves—through deliberate effort, curiosity, and reflection—is an act of resistance against the passive consumption of pre-packaged answers. And education —how we come to knowledge— is something precious for us to share with one another. Even if, while we educated one another, we have imperfect scientific knowledge (and AI would perhaps excel more reliably across disciplines), it is we who must share in Plato’s noesis together, sharing the knowledge in the context of the mysterious and meaningful whole.

I’m writing this from Oxford, England, where I am visiting with some very alive and active minds, including the Christian mathematician John Lennox, who over lunch yesterday pointedly reminded me that everyone has a belief, even the atheists, who believe firmly that there is no spiritual life (see his debate with Richard Dawkins). For the mathematician Lennox, that the spiritual must be discussed and articulated as much as anything else, is an absolute.

It made me think of this quote by Thomas Aquinas:

nihil enim scitur nisi verum, quod cum ente convertitur

-Aquinas

Nothing is known except truth — and this knowing is the same as being. Or: “Further, a teaching can be concerned only with being, for nothing can be known, save what is true; and all that is, is true.”

While you think about what Aquinas meant about being and knowing, contrast the Giacometti scribble with this image of the Madonna and child, carved into wood. It, too, has a simplicity —perhaps a deeper simplicity than the Giacometti, thanks to the medium of wood and the subject of holy mother and child.

Madonna and child, carved wood block. (1500s, unknown)

I am not Catholic, so this image does presumably less for me than for practicing Catholics, but it is nevertheless moving, because I am a mother… and motherhood is at once vulnerable, modest and mighty. It is the most profound participation-in-the-world that I can conceptualize. Through this participation in both the biological and the intangible / ineffable, I come to know myself, others, and the world around me more fully. It is relational in everyway. Motherhood is both human experience and human action. It cannot be replaced by a machine, even if films like I am Mother (see trailer) suggest that motherhood is merely about instructing a younger human. Which, if motherhood is merely a passing of information and a guiding, then indeed a machine might do well enough.

But mothering is a transmission of culture (which is habits, traditions, beliefs, idiosyncrasies). And all teaching should be a transmission not merely of facts or technique, but of also of customs and stories and preferences. In other words, it is a transmission of a certain amount of imagination. This is why —despite the many applications of AI for education tech— I am always going to advocate for education to involved as small a ratio between master and apprentice (teacher : student) as possible.

During our homeschooling years: the children at a place of worship and history (built in the 7th century AD)

We are not in a time of masters and apprenticeships, and not even of grandparents and other family members intent on passing on their knowledge and beliefs. We have thought leaders and influencers, whose content —freed from the limitations of am grateful for the many popular thought leaders who have in recent years come to take earnestly the ideas of faith. At very least, to wrestle with the ideas. Atheists like Richard Dawkins have debated ex-atheists like Ayan Hirsi Ali, while popular writers, columnists, and podcasters have done the unthinkable—hosted believers and let them speak about their faith. The current wrestling itself is at very least an important admission that we simply do not know. We do not know spiritual reality. But we are forced to respond: and whether following or rejecting, if there is to be any relief from the tension in the decision, there must be a leap.

All the things we can’t take with us. (Photograph. Wallhoff. 2016.)

This photo captures various art works and artifacts at the home of a man who was comfortable making the leap to believe in the reality of God, though he shied away from specific doctrine. He passed away recently, but what he transmitted to me was an insistence on participating in life, on loving life, and on holding the tension between calculating and imagining. He was in awe of life and wanted to understand it, without reducing it. He pushed me to understand Eric Kandel’s work (read In Search of Memory), to understand the mind. But he would not be enthralled by our widespread enthusiasm for artificial intelligence as the replacement for our minds. He would surely say that we are eliminating awe and a sense of the mystery of it all. He insisted on time spent outdoors, where he felt smaller, and felt he had a better sense of the Whole.

Giacometti spent plenty of time outside; he live in Switzerland’s southeast mountains, creating pieces that often showed man reduced to a stick figure, wandering through the world. Today, other artists continue to wander in those wild and jagged places of the Alps, questioning who we are as individuals in relation to others. One such is Patrick Salutt, who will show at NOMAD this year for the first time. His latest works are largely personal —either self portraits or portraits of his mountain people. There is a simplicity to the paint application, but the pieces have a life and restlessness in them that depict the relationship between what is seen, what is felt, what is known, and what is believed.

The NOMAD catalogue this year ends with this quote from Mann:

“In every human heart there is a longing for immortality, a desire to leave a mark upon the world after we are gone.” — The Magic Mountain, Thomas Mann

And why is there a longing for immortality? We sense eternity because we are built in relationship to something far more profound than the mere facts around us. And thank God for art, because it is the expression of the freedom we have, to express beyond words what participation, knowing, belief, identity, and living are.